Ethics, the Individual as a Philosopher of the Self, The Cosmos & the State - An Introduction

Ethics an Introduction

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of light, it was the season of darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair.” In the beginning lines of "A Tale of Two Cities," it was Charles Dickens who so eloquently captured the seemingly paradoxical nature of the human psyche. The human, capable of follies and wonders, set on a quest to explore the multitudinous pathways that lead to evil and good courses of action. Actions that reflect the tumultuous evolution of ethics over time, encapsulating behavioral changes across the millennium. Plato once said: “Human behaviour flows from three main sources: desire, emotion, and knowledge.” With the evolution of the human species the innate biological predicament for individual self-preservation spearheaded the continuous exploration and consequently comprehension of our inner psyches—our desires and emotions. This quest for knowledge propelled a gaging with the desires, motives and feelings of the individual, the community and by extension the environment surrounding the individual giving birth to humanitarian and scientific disciplines, including the natural sciences, astronomy, and physics, psychology and philosophy --ethics can be viewed as the cognitive framework overseeing the self-regulated disciplines of the humanities and sciences. It establishes the groundwork for not only discerning the purpose behind each pursuit of knowledge—how it is acquired, utilized, and applied—but also for addressing the perennial, at times existential, question of how one ought to live and by extension how one ought to understand and manage their desires and emotions and the consequent perceptions of the self and the world.

The Philosopher

Given the context, historical time, personal perspective and already acquired knowledge and experience many philosophers, different civilizations and significant individuals have sought to answer this question and the very many questions arising at the aftermath of that main concept as they are reflected through different disciplines. The quest, concepts and discussions whilst remaining the same are also reexamined differently and refined in accordance to the presentation of new information. Good and evil courses of actions, just and unjust, moral, and immoral thereof exist on a spectrum. In the realm of every new historical period in the Anthropocene era several moral standards have been subject to alterations. Even though in general as a collective certain objective, universal standards of ethics might to an extent apply they are also to a different degree malleable to change. The reasons are many and complicated and involve multiple stakeholders from different facets of society nonetheless it is important to assess when, how, why it happens as well as how malleable and susceptible to leniency they have become and why that is the case from an economic and sociopolitical standpoint. The evolution of practical ethics over time acts more as a reflection reflecting changes in society, encapsulating societal perspectives and responses to socio-political dynamics and less than an active moral compass in individual and collective decision making.Philosophers, however, envision an ideal societal structure and outline strategies to achieve it.

Socrates

Socrates believed that true knowledge is essential for just rulership. In Book V of the Republic, Socrates asserts that philosophers, who are devoted to the pursuit of wisdom and truth, are the only ones fit to govern. This is because they understand the Form of the Good, the ultimate standard of justice and morality. Socrates' famous dictum, “The unexamined life is not worth living” (Apology, 38a), reflects his belief that self-reflection and ethical inquiry are essential for anyone, especially those in positions of power. Ethical rulers must constantly question their actions, motives, and principles to ensure they govern justly.

Plato

Plato argued that society will only achieve justice and harmony when philosophers—those who possess wisdom, reason, and a deep understanding of the Forms, especially the Form of the Good—are in positions of power. He believed philosophers were uniquely qualified to govern because they were not motivated by personal gain, but rather by the pursuit of truth and the common good.

In the Ship of State Analogy (Book VI): Plato used this analogy to illustrate his point. He compared a state to a ship where the true navigator (the philosopher) is ignored, while others without knowledge of navigation (politicians and opportunists) compete for control. This highlights the necessity of entrusting governance to those with knowledge.

In the Allegory of the Cave (Book VII): Plato argued that philosophers are like individuals who have escaped the "cave" of ignorance and perceived the true nature of reality. They have a moral duty to return to the cave (the society) and share their knowledge to guide others toward the good life.

Aristotle:

Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics does touch on the idea of governance and leadership, but his approach was distinct from Plato’s Republic. While Plato advocated for governance by philosopher-kings who are primarily driven by knowledge of the Forms, Aristotle emphasized governance grounded in practical wisdom (phronesis) and ethical virtue. Both philosophers recognised the importance of wisdom in governance but framed it through different lenses: Plato's more idealistic and metaphysical approach versus Aristotle's practical and ethical framework.

In Nicomachean Ethics (Book VI), Aristotle described practical wisdom (phronesis) as the intellectual virtue that enables individuals to make sound decisions about how to live well and act rightly. For Aristotle, a good ruler must possess phronesis because this virtue combines knowledge of ethical principles with the practical ability to apply them to particular situations. In Nicomachean Ethics (Book I), he argued that politics is the "master science" because it aims at the highest good for the community. A ruler, therefore, must have ethical virtue and wisdom to guide society toward eudaimonia (human flourishing or the good life). Leaders, as ethical role models, should themselves embody the virtues they wish to encourage in others.

At its best, ethics serves as a compass with the intention to generate positive impacts. Values delineate the aspirational ideals that underpin decision-making, while virtues cultivate the moral character necessary for the pursuit of the common good at its worst ethics is a disregarded set of decisions often maligned to exert solely self-serving purposes masked as beneficial for the wider community. Despite this tumultuous evolution, the purpose of ethics fundamentally lies in the preservation and propagation of societal harmony. Opinions amongst philosophers exist within a spectrum.

Niccolo Machiavelli:

In The Prince, Machiavelli took a realist approach to governance, arguing that rulers must focus on power and stability rather than idealised morality.While he separated personal ethics from political necessity, he did stress that rulers must appear virtuous to maintain power and legitimacy.His ideas sparked debate on whether ethical principles can (or should) guide statecraft in a world driven by conflict and ambition.

“It is not necessary for a prince to be good, but it is necessary to appear so.”

Thomas Hobbes:

Hobbes, in Leviathan, argued that humans are naturally self-interested and exist in a "state of nature" marked by chaos and violence ("war of all against all").

- To escape this, individuals agree to a social contract, surrendering their freedom to a powerful sovereign who enforces order and security.

- Hobbes' ruler (the Leviathan) is not necessarily virtuous but is essential for preventing societal collapse. Ethics in governance here prioritised peace and stability over individual liberty.

John Locke:

Locke, in Second Treatise of Government, argued that legitimate governance arises from a social contract to protect individuals' natural rights: life, liberty, and property.He insisted that rulers must govern ethically by respecting these rights and ensuring the common good. If a government becomes tyrannical, the people have the moral right to overthrow it.

“Where there is no law, there is no freedom.”

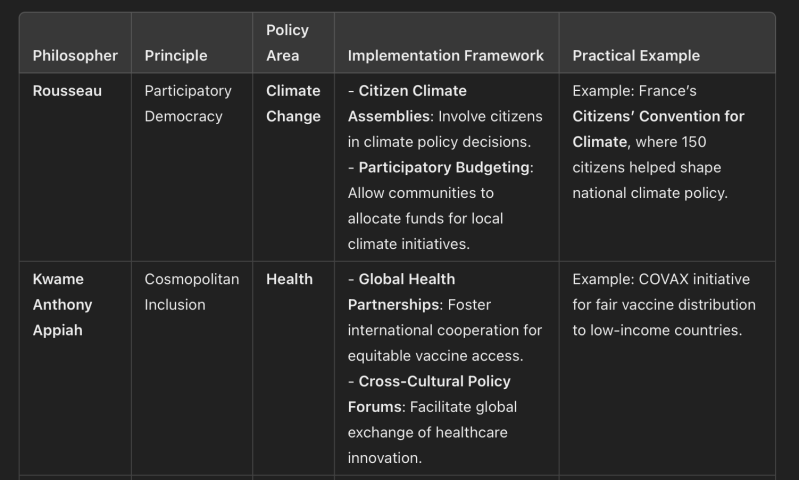

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

In The Social Contract, Rousseau critiqued corrupt governments and advocated for a political system based on the general will—the collective moral good of the people. True governance, he argued, must be rooted in virtue, equality, and freedom. Unlike Hobbes, Rousseau believed humans are naturally good but corrupted by society. Ethical rulership must align with the general will, ensuring that citizens are both free and virtuous.

“Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains.”

Immanuel Kant

Kant integrated ethics and politics through his concept of moral duty and universal principles. In Perpetual Peace, he argued for governments based on republican constitutions and respect for individual freedom.Ethical governance, for Kant, involves treating individuals as ends in themselves, not as means to an end (from his categorical imperative). Kant also advocated for international peace through moral and legal agreements between states.

“Act only according to that maxim by which you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law.”

Hegel:

Hegel viewed the state as the highest expression of ethical life (Sittlichkeit). In his Philosophy of Right, he argued that the state embodies rationality, freedom, and morality.True ethical governance arises when individuals recognize their roles as part of a larger moral community. The state, when properly organized, promotes the realization of human freedom.

“The State is the march of God on Earth.”

John Stuart Mill

Mill, a utilitarian thinker, argues that ethical governance should maximize happiness for the greatest number of people. In On Liberty, he emphasizes the importance of protecting individual freedoms and limiting state power to prevent tyranny. Mill believes ethical governance balances individual liberty with the common good.

“The worth of a state in the long run is the worth of the individuals composing it.”

Summary: Post-Mill Philosophers on Ethics and the State

These thinkers address ethical governance in the context of modern challenges: class struggle, democracy, totalitarianism, globalization, and human rights. They reflect evolving ideas of justice, freedom, and power in increasingly complex societies.

Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900) – Beyond Traditional Morality

-

Nietzsche challenges traditional morality and ethical frameworks (including those used to justify governance), arguing that they suppress human potential.

-

He critiqued modern states as imposing herd morality, which stifles individual excellence and the “will to power.”

-

Nietzsche’s ideas about self-overcoming and questioning values influenced 20th-century political thought but did not offer a direct model for governance.

Max Weber (1864–1920) – The Ethics of Responsibility

-

Weber, in Politics as a Vocation, distinguished between two types of ethics in governance:

- Ethics of Conviction: Acting based on absolute moral principles (e.g., Kantian duty).

- Ethics of Responsibility: Taking into account the consequences of actions and the practical realities of power.

-

Weber argued that ethical governance involves balancing moral convictions with pragmatism and accepting the complexities of political leadership.

“Politics is a strong and slow boring of hard boards.”

John Dewey (1859–1952) – Pragmatism and Democracy

-

Dewey, a pragmatist philosopher, advocated for participatory democracy where citizens actively shape governance through education and ethical deliberation.

-

In Democracy and Education, he argued that ethical governance is grounded in fostering critical thinking and social cooperation.

-

Dewey saw the state as an evolving institution that must address social problems and promote the public good.

“Democracy is more than a form of government; it is primarily a mode of associated living.”

Hannah Arendt (1906–1975) – Ethics, Power, and Totalitarianism

-

Arendt, in The Origins of Totalitarianism and The Human Condition, examined how ethical governance breaks down under totalitarian regimes.

-

She argues that ethical politics requires active citizen engagement and respect for human dignity.

-

Arendt emphasized the importance of plurality—acknowledging diverse perspectives within the public sphere—as the foundation for ethical governance.

“The essence of politics is freedom.”

John Rawls (1921–2002) – Justice as Fairness

-

Rawls, in A Theory of Justice, introduced the concept of justice as fairness, which became one of the most influential frameworks for ethical governance in the 20th century.

-

He argued that a just society is based on two principles:

- Equal basic rights and liberties for all.

- Social and economic inequalities are allowed only if they benefit the least advantaged (the “difference principle”).

-

Rawls used the veil of ignorance as a thought experiment to determine fair principles of governance: individuals design a just society without knowing their place in it.

“Justice is the first virtue of social institutions.”

Robert Nozick (1938–2002) – Libertarian Ethics and the Minimal State

-

In Anarchy, State, and Utopia, Nozick criticized Rawls and argued for a minimal state whose sole purpose is to protect individual rights, especially property rights.

-

Ethical governance, for Nozick, involved respecting individual liberty and limiting state intervention in personal and economic affairs.

-

He argued against redistribution of wealth, viewing it as a violation of personal freedom.

Jürgen Habermas (1929–present) – Communicative Ethics and Deliberative Democracy

-

Habermas emphasized the importance of rational discourse and communication in ethical governance.

-

In The Theory of Communicative Action, he argued that legitimate political decisions arise through deliberative democracy—a process where citizens engage in open, rational debate to reach consensus.

-

Ethical governance requires transparency, mutual respect, and the inclusion of all voices in decision-making processes.

“The only norms that can claim validity are those that meet (or could meet) with the approval of all affected in their capacity as participants in a practical discourse.”

Michel Foucault (1926–1984) – Power and Ethics

-

Foucault examined how power operates in society, critiquing traditional ethical frameworks that mask underlying systems of control.

-

In works like Discipline and Punish and The History of Sexuality, he explored how states enforce norms and regulate individuals’ behavior through institutions (e.g., prisons, schools).

-

Foucault calls for individuals to resist oppressive systems and engage in an “ethics of the self,” where personal autonomy challenges state-imposed morality.

“Where there is power, there is resistance.”

Amartya Sen (1933–present) – Ethics, Capabilities, and Development

-

Sen, in Development as Freedom, expands ethical governance to include global justice and economic development.

-

He emphasizes the capabilities approach, which measures justice and governance based on individuals’ ability to lead lives they value.

-

Sen argues that ethical governance must prioritize expanding freedoms, reducing poverty, and ensuring access to education, healthcare, and opportunity.

“Poverty is not just lack of money; it is not having the capability to realize one’s full potential as a human being.”

Ethics in the Context of Modernisation

Contemporary philosophical thinkers continue to grapple with ethics and governance, addressing urgent issues such as inequality, justice, diversity, globalisation, technology, and climate change. Scholars like Sophia Ribenstein Moreau reflect modern concerns surrounding discrimination, moral agency, and institutional ethics.

Here’s a look at current thinkers, including Moreau, and their contributions:

Sophia Moreau – Discrimination, Justice, and Equality

-

Key Themes: Ethics of Discrimination, Moral Harm, Equality

-

Moreau, in works like Faces of Inequality: A Theory of Wrongful Discrimination, examines how discrimination impacts individuals beyond economic consequences.

-

She argues that wrongful discrimination is multidimensional, harming people’s self-respect, autonomy, and their ability to participate as equals in society.

-

Her work connects ethical governance to addressing structural and systemic inequalities, particularly in legal and institutional contexts.

Relevance: In modern governance, her framework supports policies that address intersectionality and recognize the multifaceted harm caused by discrimination.

Amia Srinivasan – Feminism, Power, and Epistemic Injustice

-

Key Themes: Feminist Ethics, Power Dynamics, Knowledge

-

Srinivasan explores the intersection of ethics, politics, and knowledge systems. In The Right to Sex, she examines how structural power shapes intimate and societal relationships.

-

She critiques how governance systems reinforce inequality by ignoring the ethical dimensions of power in private and public spaces.

-

Her work connects ethical governance to addressing epistemic injustice—the ways marginalized voices are excluded from knowledge creation and decision-making.

Relevance: Ethical governance must prioritize inclusive participation and dismantle harmful norms embedded in institutions.

Martha C. Nussbaum – Capabilities, Justice, and Human Flourishing

-

Key Themes: Capabilities Approach, Human Rights, Justice

-

Nussbaum’s work builds on Amartya Sen’s capabilities approach. In Frontiers of Justice and Creating Capabilities, she argues for ethical governance that enables individuals to lead lives they value.

-

She identifies ten central capabilities (e.g., health, education, emotional well-being) that governments must promote to achieve justice.

-

Nussbaum also applies her theories to animal ethics, global inequality, and disabilities, expanding the scope of governance.

Relevance: Her work serves as a framework for policies that prioritize human dignity, equality, and social welfare.

Kwame Anthony Appiah – Cosmopolitanism, Identity, and Moral Responsibility

-

Key Themes: Cosmopolitan Ethics, Global Justice, Identity

-

In Cosmopolitanism: Ethics in a World of Strangers, Appiah argues for governance rooted in global solidarity and shared moral values, while respecting cultural diversity.

-

He critiques governance systems that fail to address global inequality and environmental crises.

-

Appiah’s ethical approach emphasizes finding common ground while respecting pluralism and individual identities.

Relevance: His ideas inform ethical governance in addressing globalization, climate justice, and international cooperation.

Charles Mills (1951–2021) – Racial Justice and the State

-

Key Themes: Race, Power, Social Contract, Justice

-

Mills, in The Racial Contract, argues that traditional social contract theories (e.g., Hobbes, Locke) perpetuate racial inequalities by excluding non-white individuals from the moral and political community.

-

He critiques systems of governance that maintain structural racism and calls for ethical frameworks that address historical injustices.

Relevance: Modern governance must confront systemic racism and pursue policies that achieve meaningful reparations and racial justice.

Elizabeth Anderson – Egalitarianism and Workplace Justice

-

Key Themes: Relational Equality, Ethical Workplaces, Democracy

-

Anderson, in Private Government and The Imperative of Integration, critiques economic systems that undermine workers' autonomy and equality.

-

She argues for ethical governance that addresses workplace oppression and promotes democratic equality.

-

Anderson emphasizes creating institutions that foster respect, dignity, and inclusivity.

Relevance: Her work informs debates about labor rights, corporate ethics, and democratizing workplaces.

Judith Butler – Power, Gender, and Governance

-

Key Themes: Gender Ethics, Vulnerability, Resistance

-

Butler critiques systems of governance that reinforce gender norms and marginalize vulnerable populations.

-

In Notes Toward a Performative Theory of Assembly, Butler connects ethics and governance to collective resistance movements, advocating for political systems that recognize human precarity.

Relevance: Ethical governance must address the needs of marginalized groups and support policies that promote inclusion and human rights.

Thomas Pogge – Global Justice and Poverty

-

Key Themes: Global Ethics, Institutional Reform, Inequality

-

Pogge, in World Poverty and Human Rights, argues that global economic systems are unjust, as they exacerbate poverty and inequality.

-

He proposes institutional reforms that ensure ethical governance addresses the root causes of global poverty and distributes resources more equitably.

Relevance: Pogge’s work influences ethical governance policies aimed at global economic justice.

Cécile Fabre – Ethics of War, Humanitarian Intervention, and Resources

-

Key Themes: Just War Theory, Global Ethics, Resources

-

Fabre examines ethical governance in the context of international conflict, humanitarian intervention, and resource allocation.

-

She argues that ethical governance involves respecting human rights during war and ensuring fair distribution of global resources.

Relevance: Her work is essential for understanding ethical responses to international crises and governance in a globalized world.

Peter Singer – Ethics of Altruism, Governance, and Climate Change

-

Key Themes: Utilitarian Ethics, Effective Altruism, Global Responsibility

-

Singer, in The Life You Can Save and Practical Ethics, advocates for ethical governance that prioritizes reducing global suffering.

-

He connects ethics to practical issues like climate change, animal welfare, and poverty, emphasizing the responsibility of affluent nations.

Relevance: Singer’s ideas shape modern governance strategies for global development and environmental sustainability.

Emerging Themes in Current Philosophy on Ethics and Governance

Contemporary philosophers focus on:

- Global Justice: Addressing inequality, climate change, and international cooperation.

- Identity and Inclusion: Tackling discrimination, systemic oppression, and intersectionality in governance.

- Technology and Ethics: Considering AI governance, surveillance, and digital ethics.

- Environmental Ethics: Sustainable policies for planetary well-being.

- Power and Vulnerability: Challenging systems of domination and promoting collective action.

Sophia Moreau’s work exemplifies this shift toward recognizing the complex harms caused by discrimination and the need for ethical frameworks that create just, inclusive, and equitable systems of governance. Alongside other thinkers, she contributes to a more holistic and modern approach to ethics and the state.

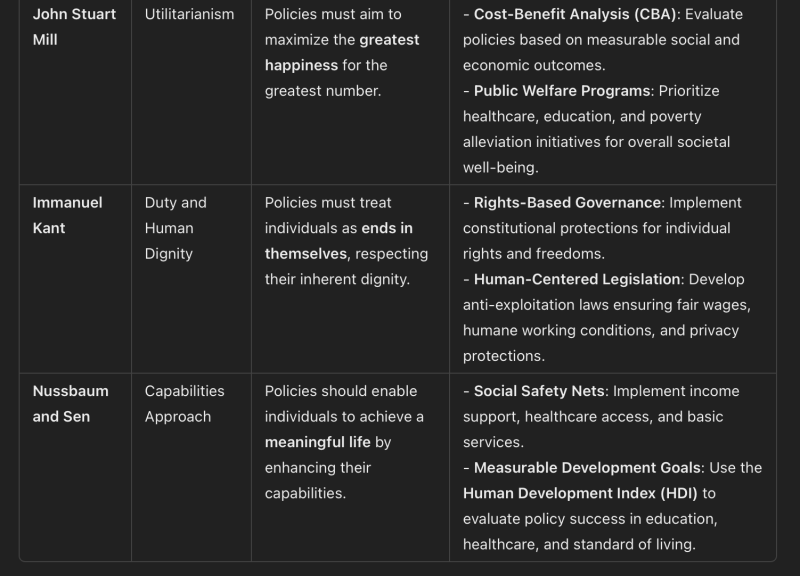

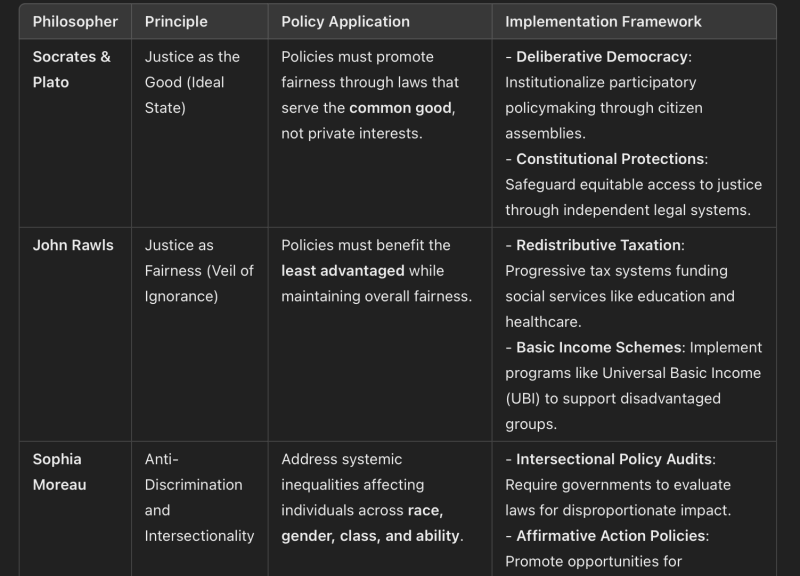

From Ethics to Policy: A look at tangible general Governance Frameworks Part I

Fundamentals Principles

Justice and Equality

Moral Accountability of Leadership

Inclusive Participation and Democracy

Global Responsibility and Sustainability

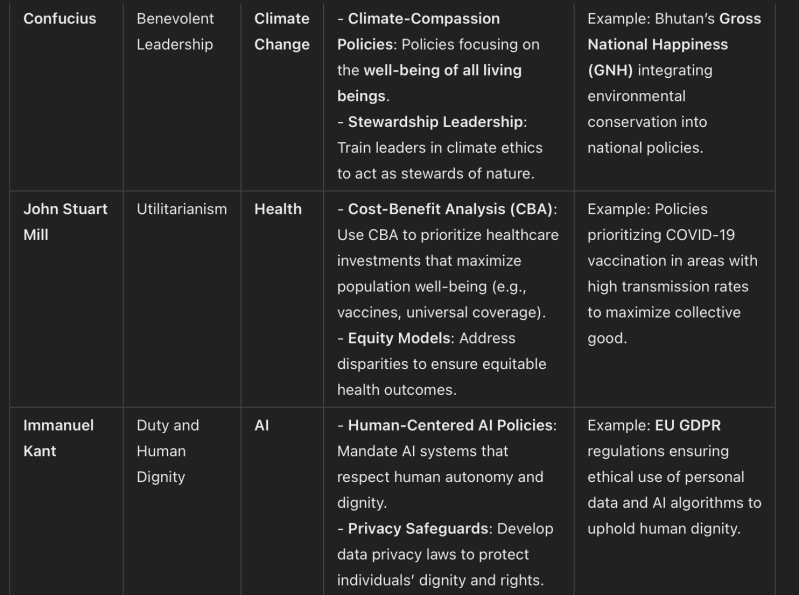

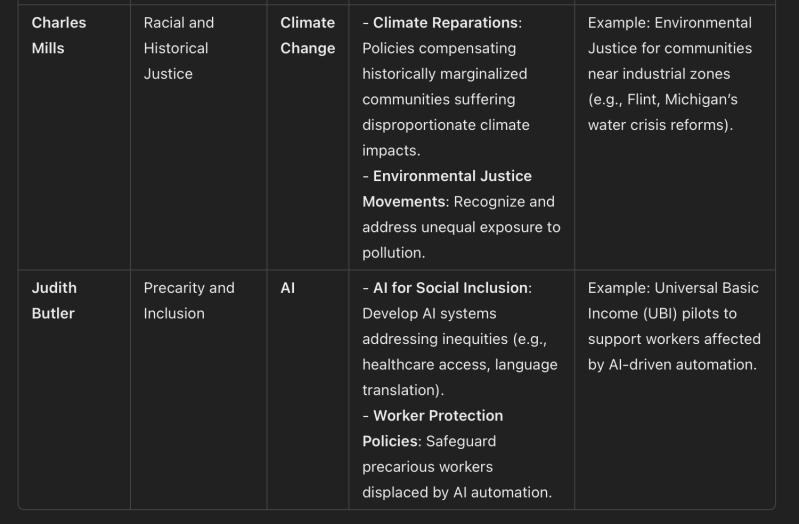

From Ethics to Policy: A look at tangible general Governance Frameworks Part II: AI, Health, Climate

Foundational Principles

Justice and Equality

Moral Accountability and Leadership

Inclusive Participation and Democracy

Global Responsibility and Sustainability

Governance Solutions in Tech Part I : The promise of Web 3.0: From Centralisation to Decentralisation and Beyond

The transition to blockchain and Web 3.0 is more than a technological shift; it represents a philosophical, economic, and political evolution towards greater decentralisation, transparency, and inclusivity. By embedding democratic principles and ethical governance into the digital fabric, these technologies offer pathways to address contemporary challenges in democracy, economic inequality, and global governance. Through this lens, blockchain and Web 3.0 can be seen as foundational tools for constructing a more just and equitable future.

Philosophical, Economic, and Political Analysis of Blockchain and Web 3.0

Philosophical Dimension

-

Decentralization and Empowerment:

- Philosophical Roots: Rooted in Enlightenment ideals of autonomy and freedom, blockchain and Web 3.0 aim to decentralize power structures. Philosophers like Immanuel Kant emphasised individual autonomy and moral self-governance, which aligns with the ethos of decentralisation.

- Ethical Framework: Blockchain embodies a trustless system where governance is based on consensus rather than centralised authority. This echoes Jean-Jacques Rousseau's concept of the "general will," where collective decision-making aligns with communal interests.

- Digital Sovereignty: As data becomes a critical resource, the ethical argument for personal data sovereignty grows. Blockchain empowers individuals to own and control their data, shifting the paradigm from corporate ownership to personal autonomy.

-

Transparency and Accountability:

- Philosophical Roots: Inspired by the philosophies of accountability seen in thinkers like Jeremy Bentham, blockchain's immutable ledger promotes transparency, reducing corruption and fostering trust in systems.

- Democratic Ethos: The transparency inherent in blockchain systems aligns with democratic principles, allowing all participants equal access to information, reminiscent of John Rawls' "veil of ignorance" which promotes fairness and impartiality in governance.

Economic Dimension

-

Disintermediation:

- Economic Theory: Blockchain eliminates intermediaries, reducing transaction costs and increasing efficiency. This reflects Adam Smith's advocacy for free markets where direct transactions benefit the economy by reducing unnecessary overhead.

- Decentralized Finance (DeFi): By removing central banking control, DeFi fosters economic inclusion, offering access to financial services to the unbanked and underbanked populations. This mirrors Hayek's ideas on decentralizing economic control to prevent centralized abuse.

-

Tokenization and New Economic Models:

- Innovation in Property Rights: Tokenization enables fractional ownership, democratizing access to assets like real estate and intellectual property. This represents a shift towards more inclusive capital markets, aligning with modern reinterpretations of Karl Marx’s critique of capital concentration.

- Universal Basic Income (UBI): Blockchain can support UBI distribution through smart contracts, ensuring transparent and efficient redistribution of wealth, reflecting contemporary efforts to address income inequality as discussed by economists like Thomas Piketty.

Political Dimension

-

Democratization of Governance:

- Political Philosophy: Blockchain supports decentralized governance structures like Decentralized Autonomous Organizations (DAOs), embodying direct democracy principles where participants have a direct say in decision-making, reminiscent of Athenian democracy.

- Participatory Governance: By enabling stakeholder participation, DAOs ensure that governance is inclusive and democratic, addressing the political alienation critiqued by thinkers like Jürgen Habermas.

-

Global Governance and Sovereignty:

- Political Theory: Blockchain challenges traditional notions of sovereignty by enabling borderless governance models. This aligns with Immanuel Kant's vision of a cosmopolitan order where global cooperation supersedes national interests.

- Resilience and Decentralization: In a world of increasing geopolitical instability, blockchain offers a resilient infrastructure for governance and finance, reducing dependence on centralized institutions and reflecting the anarchist critiques of state power by figures like Mikhail Bakunin.

Solutions at a Democratic and Ethical Level

-

Enhanced Civic Engagement:

- Blockchain can power decentralized voting systems, increasing participation and reducing electoral fraud. This promotes a more engaged and informed citizenry, key to vibrant democracies.

-

Ethical Governance and Accountability:

- Smart contracts enforce rules and policies transparently, ensuring accountability. This reduces the scope for corruption, aligning with modern governance standards advocating for integrity and ethical leadership.

-

Economic Justice and Inclusion:

- Blockchain enables financial inclusion, democratizing access to economic resources and opportunities, aligning with social justice principles. This offers marginalized communities access to global markets and fair economic participation.

-

Sustainable Development:

- Blockchain can enhance transparency in environmental governance, tracking carbon credits, and ensuring accountability in corporate sustainability efforts. This aligns with global ethical commitments to climate action.

Governance Solutions in Tech Part II: Living in the Age of AI

Artificial Intelligence represents a transformative force in society, with profound philosophical, economic, and political implications. Its development and integration require thoughtful governance frameworks that prioritise ethical considerations, economic inclusivity, and democratic principles. By aligning AI's capabilities with human values and societal goals, we can harness its potential for positive change while mitigating risks and ensuring a just and equitable future.

Connecting the Dots..... A brief Philosophical, Economic, and Political Analysis of Artificial Intelligence (AI)

Philosophical Dimensions

-

Ethics of Autonomy and Responsibility:

- Philosophical Roots: AI challenges traditional notions of autonomy and moral responsibility. Thinkers like Immanuel Kant emphasized autonomy as a cornerstone of moral agency, but AI systems, acting autonomously, complicate accountability frameworks.

- Ethical AI: The debate centers around ensuring AI systems align with human values, inspired by Aristotle's virtue ethics, which promotes the development of moral character. The challenge is embedding ethical reasoning within AI to ensure actions promote human flourishing.

-

Human-Machine Interaction:

- Philosophical Roots: AI blurs the line between humans and machines, raising existential questions about what it means to be human. This echoes the concerns of existentialist philosophers like Jean-Paul Sartre, who emphasized human freedom and the authentic self.

- AI and Human Dignity: There is a need to ensure AI enhances rather than diminishes human dignity, reflecting the humanist concerns of thinkers like Martha Nussbaum, who advocate for capabilities that allow humans to lead meaningful lives.

Economic Dimensions

-

Automation and Employment:

- Economic Theory: AI-driven automation has the potential to disrupt labor markets, reminiscent of the Industrial Revolution's impact. The concern is whether AI will create or displace jobs and how economic systems adapt.

- Redistribution and UBI: Economists like John Maynard Keynes predicted technological unemployment, suggesting policies like Universal Basic Income (UBI) as a buffer. AI-driven productivity gains could fund social welfare programs to redistribute wealth more equitably.

-

AI-Driven Economic Growth:

- Innovation and Efficiency: AI promises significant efficiency gains, driving economic growth. This aligns with Joseph Schumpeter's theory of creative destruction, where AI acts as a disruptive force that reshapes industries and creates new markets.

- Economic Inequality: The wealth generated by AI could exacerbate inequality if concentrated among tech giants. Addressing this requires policies inspired by Piketty’s focus on wealth redistribution and progressive taxation to ensure broad-based benefits.

Political Dimensions

-

Governance and Regulation:

- Political Philosophy: The rapid development of AI calls for robust governance frameworks. Theories of social contract, as discussed by Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau, are relevant in designing regulations that balance innovation with societal protection.

- Global Governance: AI transcends national borders, necessitating global cooperation akin to Immanuel Kant’s vision of a cosmopolitan order. International regulations and agreements are crucial to managing AI’s impact on global stability and security.

-

AI and Democracy:

- Democratic Participation: AI can both enhance and threaten democratic processes. While it can improve civic engagement through better data analysis and personalized communication, it also risks undermining democracy through surveillance, misinformation, and manipulation.

- Transparency and Accountability: The political challenge lies in ensuring AI systems are transparent and accountable. This reflects Jeremy Bentham's principle of accountability, where the public should have insight into how decisions affecting them are made.

Solutions at a Democratic and Ethical Levels

-

Ethical AI Development:

- Establish frameworks for ethical AI, incorporating principles from bioethics and human rights. Initiatives like AI Ethics Boards and guidelines, similar to those by UNESCO or IEEE, ensure AI development aligns with societal values and human rights.

-

Inclusive Economic Policies:

- Implement policies to manage the transition in labor markets, such as reskilling programs, social safety nets, and UBI. These measures ensure AI-driven economic changes are inclusive and beneficial to all segments of society.

-

Democratic AI Governance:

- Develop participatory governance models for AI policy-making, ensuring diverse stakeholder input, including civil society, industry, and academia. This participatory approach enhances legitimacy and public trust in AI systems.

-

Global Cooperation:

- Foster international cooperation to establish global AI governance standards. Collaborative efforts like the Global Partnership on AI (GPAI) promote shared principles and best practices, ensuring AI contributes to global public goods.

A Deeper Dive into AI

The Transition from AI to AGI and ASI

As we navigate the Intelligence Age, AI is evolving rapidly from narrow applications to the pursuit of Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) and eventually Artificial Superintelligence (ASI). This journey entails profound transformations in human capabilities, industries, and societal structures.

-

Artificial Intelligence (AI)

- Definition and Scope: AI encompasses systems capable of performing tasks requiring human-like intelligence, such as natural language processing, decision-making, and pattern recognition. Current AI technologies have revolutionized sectors like healthcare, finance, and transportation, enhancing efficiency and enabling new possibilities.

-

Artificial General Intelligence (AGI)

- Broad Capabilities: AGI represents a leap where AI systems can perform a wide array of intellectual tasks at or above human levels. Unlike narrow AI, AGI would adapt to new situations without specific programming.

- Implications: The development of AGI could redefine labor markets, spur innovation, and tackle complex global challenges. However, it also raises significant ethical and safety concerns, necessitating rigorous oversight and alignment with human values.

-

Artificial Superintelligence (ASI)

- Surpassing Human Intelligence: ASI systems would outperform human intelligence across all domains, potentially leading to an "intelligence explosion" where AI systems continuously improve themselves.

- Transformational Potential: ASI could solve problems currently beyond human reach, from eradicating diseases to addressing climate change. However, it poses existential risks if misaligned with human values or if control mechanisms fail.

Technical Foundations and Accelerating Progress

-

Core AI Concepts:

- Supervised and Unsupervised Learning: These foundational techniques enable AI systems to learn from data, either with or without labeled inputs, driving advancements in areas like image recognition and natural language processing.

- Reinforcement Learning: This method, where AI learns optimal actions through trial and error, has been pivotal in developing autonomous agents and gaming AI.

- Deep Learning and Transformers: Deep learning, particularly transformer architectures, has revolutionized AI's ability to understand and generate human-like text, enhancing applications in translation, summarization, and conversational agents.

-

Scaling and Computational Growth:

- Exponential Compute: Advances in computational power, driven by GPUs, TPUs, and architectural innovations, have accelerated AI progress. Scaling laws predict that increasing model size and training data will continue to yield significant improvements.

- Emergent Behaviors: Larger models have exhibited emergent capabilities, such as zero-shot learning, where AI can perform tasks without explicit training, indicating potential paths toward AGI.

-

Autonomous Agents and Resource Investment:

- From Passive to Active: AI is transitioning from passive models to autonomous agents capable of interacting with and learning from their environments, enhancing their utility and adaptability.

- Economic Implications: Massive investments in AI research and infrastructure underscore its perceived transformative potential, driving further advancements and applications.

Societal and Economic Transformation

-

Automation and Productivity:

- Workforce Redefinition: AI's ability to automate both routine and complex tasks could lead to unprecedented productivity gains but also significant labor market disruptions. Strategies for workforce transition and upskilling are critical.

- Economic Growth: AI-driven automation and innovation can fuel economic expansion, though the distribution of benefits must be managed to avoid exacerbating inequalities.

-

Scientific and Technological Advancements:

- Accelerated Discovery: AI's application in research can dramatically speed up scientific discovery, from drug development to materials science, enabling breakthroughs that were previously out of reach.

- Engineering Innovations: AI-driven optimization can revolutionize engineering processes, creating more efficient and sustainable technologies.

-

Healthcare and Personalized Medicine:

- Tailored Treatments: AI's ability to analyze vast amounts of genomic and clinical data can lead to personalized medicine, improving patient outcomes and healthcare efficiency.

- Drug Discovery: AI accelerates the identification of potential therapeutic compounds, reducing the time and cost associated with bringing new drugs to market.

-

Environmental Sustainability:

- Climate Change Mitigation: AI can develop innovative solutions for reducing emissions and managing environmental impacts, contributing to global sustainability efforts.

- Resource Conservation: AI algorithms optimize energy use, waste reduction, and sustainable resource management, supporting environmental conservation.

Challenges and Ethical Considerations

-

AI Safety and Alignment:

- Control and Values Alignment: Ensuring AI systems are reliable, trustworthy, and aligned with human values is paramount. Mechanisms for monitoring, managing, and, if necessary, deactivating AI systems must be developed to prevent unintended consequences.

- Goal Compatibility: Aligning AI objectives with human goals is crucial to avoid harmful outcomes, especially as AI systems become more autonomous and capable.

-

Regulatory and Security Risks:

- Balancing Innovation and Safety: Crafting policies that promote AI's benefits while mitigating risks is a complex challenge, requiring global coordination and ethical leadership.

- Misuse and Global Competition: The potential misuse of advanced AI for malicious purposes and the competitive rush for AI dominance pose significant security risks.

-

Existential Risks and Societal Impact:

- Loss of Control: The risk of superintelligent AI making decisions beyond human understanding underscores the need for robust alignment and control mechanisms.

- Cultural and Societal Adaptation: Rapid AI-driven changes may outpace society's ability to adapt, leading to ethical dilemmas and cultural shifts.

Navigating the Path Forward

-

Collaborative and Multidisciplinary Approaches:

- Inclusive Solutions: Addressing AI's challenges requires collaboration across AI research, ethics, policy, and social sciences. International cooperation is essential to ensure equitable benefits and mitigate risks.

- Transparent Practices: Openness about AI capabilities and limitations fosters trust and facilitates effective oversight, promoting ethical development and deployment.

-

Ethical Leadership and Policy Development:

- Proactive Governance: Developing policies that anticipate AI's future impacts and address potential risks is crucial for harnessing its benefits while safeguarding humanity.

- Global Coordination: Aligning national interests and fostering international collaboration are vital for implementing effective regulations and managing AI's global implications.

A deeper dive into the Ethical and Policy implications:Advanced Mitigation Risk in Digital Ecosystems for AI, AGI & ASI

Ethical Implications

A)Bias and Fairness:

1.Systemic Bias in Data: AI systems trained on historical data can perpetuate existing inequalities. For example, facial recognition technology often performs poorly on people of colour due to imbalanced training datasets.

- Focus: Developing tools for real-time bias detection and mitigation. This includes the creation of "fairness dashboards" for developers to monitor and adjust bias levels during model training and deployment.

-

Solution: Prioritizing Alignment with Human Values Embedding ethical principles and human values into AI systems ensures they serve the public good and adhere to societal norms:

- Ethical AI Frameworks: Adopting frameworks such as the IEEE Global Initiative on Ethics of Autonomous and Intelligent Systems to guide the integration of human values into AI design.

- Main Idea: Microsoft’s AI principles emphasise fairness, reliability, safety, privacy, security, inclusiveness, transparency, and accountability.

- Possible Tangible Frameworks:

- IEEE’s Ethically Aligned Design (EAD): A set of recommendations for ethical AI development.

- Value-Sensitive Design (VSD): Implementing VSD principles to ensure that the development of AI systems reflects the values and priorities of diverse user groups, promoting inclusivity and equity.

- Main Idea: Designing AI for healthcare applications that prioritise patient autonomy, privacy, and informed consent.

- Possible Tangible Frameworks:

- VSD Framework: Integrates ethical considerations throughout the technology design lifecycle.

- Ethics Impact Assessments (EIA): Conducting regular EIAs to evaluate the ethical implications of AI applications and ensure they align with societal values.

- Main Idea: AI systems in hiring processes can undergo EIA to evaluate potential biases and ensure fairness.

- Possible Tangible Frameworks:

- AI Ethics Impact Assessment (AI-EIA): A structured process for assessing the ethical implications of AI systems.

B)Privacy and Data Sovereignty:

1.Surveillance Risks: The rise of AI-driven surveillance poses significant threats to privacy, with governments and corporations potentially exploiting personal data for control and profit.- Focus: Advancing privacy-enhancing technologies like homomorphic encryption, which allows data processing without exposing the data itself. Strengthening the legal frameworks around consent and data sharing.

-

Solution: Implementing Secure and Privacy-Preserving Techniques Security and privacy are foundational to the integrity of decentralised AI systems. The implementation of advanced techniques ensures data protection and trustworthiness:

- Main Idea: Zero-Knowledge Proofs (ZKP): Utilising ZKP to enable systems to validate transactions and operations without exposing underlying data, thereby enhancing privacy.

- Possible Tangible Frameworks:

- ZK Frameworks (zk-SNARKs, zk-STARKs): Provide methodologies for implementing ZKPs in decentralized applications.

- Federated Learning: Leveraging federated learning to train models across decentralised nodes without transferring raw data. This minimises privacy risks while maintaining robust model performance.

- Main Idea: Google’s implementation of federated learning in its Gboard keyboard allows model training across user devices without centralised data collection.

- Possible Tangible Frameworks:

- TensorFlow Federated (TFF): A framework for experimenting with federated learning algorithms.

- Homomorphic Encryption: Applying homomorphic encryption allows computations on encrypted data, safeguarding sensitive information throughout the processing cycle.

- Main Idea: IBM’s use of homomorphic encryption enables secure data processing in the cloud without exposing sensitive data.

- Possible Tangible Frameworks:

- HElib: An open-source library for homomorphic encryption.

- 2.Transparency and Accountability:

- Algorithmic Transparency: Lack of transparency can lead to mistrust and misuse of AI. For example, credit scoring algorithms may deny loans without clear reasoning.

- Focus: Developing legislation that mandates transparency in AI systems, such as requiring companies to provide clear, understandable explanations for algorithmic decisions that impact users.

- Possible Tangible Frameworks:

- Main Idea: Zero-Knowledge Proofs (ZKP): Utilising ZKP to enable systems to validate transactions and operations without exposing underlying data, thereby enhancing privacy.

- Focus: Advancing privacy-enhancing technologies like homomorphic encryption, which allows data processing without exposing the data itself. Strengthening the legal frameworks around consent and data sharing.

- AI Ethics Impact Assessment (AI-EIA): A structured process for assessing the ethical implications of AI systems.

Solution: Encouraging Transparency and Auditability Designing AI systems with transparency and auditability is crucial for fostering trust and accountability:

- Explainable AI (XAI): Incorporating XAI methods to ensure that decision-making processes within AI systems are understandable and interpretable by stakeholders. This enhances trust and facilitates regulatory compliance.

-

Main Idea: DARPA’s XAI program focuses on creating machine learning techniques that produce more explainable models while maintaining a high level of learning performance.

- Possible Tangible Frameworks:

- LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations): Provides interpretable explanations for AI model predictions.

- SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations): A unified framework for interpreting predictions of machine learning models.

- Possible Tangible Frameworks:

- Blockchain for Audit Trails: Utilizing blockchain technology to create immutable records of AI system operations. This ensures an auditable trail, which is vital for accountability and compliance audits.

- Main Example: Estonia uses blockchain technology for secure and transparent public services, which includes medical records and legislative processes.

- Possible Tangible Frameworks:

- Hyperledger Fabric: An open-source blockchain framework providing transparency and auditability in decentralized systems.

- Transparency Reports: Regularly publishing transparency reports detailing system performance, decision-making criteria, and data usage. This keeps stakeholders informed and engaged.

- Main Example: Facebook and Twitter regularly release transparency reports detailing governmental data requests, content moderation practices, and security measures.

- Possible Tangible Frameworks:

- Global Reporting Initiative (GRI): Provides standards for transparent reporting, applicable to AI systems.

C) Autonomy and Human Agency:

- Manipulative AI Practices: Algorithms that manipulate user behavior for profit, such as engagement-maximizing algorithms on social media, can undermine personal autonomy.

- Focus: Enforcing regulations against manipulative AI practices, like dark patterns, and promoting the development of AI that enhances user control and informed decision-making.

D)Ethical Use in Sensitive Domains:

- Healthcare AI: In healthcare, the stakes are high, with AI decisions potentially impacting life-or-death situations.

- Focus: Establishing ethical guidelines specific to AI in healthcare to ensure decisions are accurate, unbiased, and enhance patient outcomes.

E) Environmental Ethics:

- Sustainability Concerns: The environmental cost of AI and blockchain technologies is significant, with large-scale data centers consuming vast amounts of energy.

- Focus: Promoting the development of energy-efficient algorithms and advocating for the use of renewable energy sources in data centers.

- Global Reporting Initiative (GRI): Provides standards for transparent reporting, applicable to AI systems.

Policy Implications

A)Regulatory Frameworks:

1) Focus: Establishing Governance Frameworks

Solution: Developing robust governance frameworks is critical for ensuring that decentralised AI systems operate within well-defined ethical and operational boundaries. Sophisticated approaches include:

- Multi-Layered Governance Structures: Implementing a tiered framework that integrates local, national, and international regulations. This approach ensures compliance with varying jurisdictional requirements and promotes interoperability across borders.

- Main Example: The European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) serves as an overarching framework, while individual member states have specific adaptations. Decentralized AI governance can mirror this model, where global standards coexist with local adaptations to accommodate regional legal and cultural nuances.

- Possible Tangible Frameworks:

- COBIT (Control Objectives for Information and Related Technologies): Offers a comprehensive framework for developing, implementing, monitoring, and improving IT governance and management practices.

- NIST AI Risk Management Framework (AIRMF): Provides guidance on managing AI risks through policies, standards, and guidelines.

- Ethical Oversight Committees: Establishing committees comprised of ethicists, technologists, legal experts, and community representatives to oversee AI development and deployment. These committees can provide continuous ethical audits and ensure adherence to best practices.

- Main Example: Google’s AI Ethics Board was formed to provide ethical oversight on AI projects, though it faced challenges and controversy, highlighting the need for transparent and accountable structures.

- Possible Tangible Frameworks: Ethical Principles of AI (UNESCO): Guidelines on ethical issues and principles for AI development and deployment.

- Adaptive Regulations: The dynamic nature of AI requires regulations that can evolve with technological advancements. Static regulations risk becoming obsolete quickly.

- Regulatory Sandboxes: Creating controlled environments for testing new AI technologies under regulatory oversight. This allows for iterative learning and refinement of governance practices before full-scale deployment.

- Main Example: The UK’s Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) sandbox allows fintech companies to test innovative products under regulatory supervision, which could be adapted for decentralized AI projects.

- Possible Tangible Frameworks: Regulatory Sandboxes Framework (World Economic Forum): Outlines best practices for creating environments that foster innovation while ensuring regulatory compliance.

- 2.Ethical AI Certification:

- Standardization Challenges: Currently, there's a lack of consensus on what constitutes "ethical AI," leading to fragmented and inconsistent practices.

- Focus: Creating international standards for ethical AI certification, akin to ISO standards, that organizations can adopt to demonstrate compliance with ethical norms.

3.Labor and Economic Impact:

- Job Displacement: Automation can lead to significant job loss, particularly in low-skill sectors, exacerbating economic inequalities.

- Focus: Implementing policies that promote job retraining and upskilling in AI-related fields, alongside measures to support workers transitioning from automated roles.

4.Global Cooperation and Governance:

- Fragmented Governance: The absence of a unified global framework for AI governance can lead to disparities in ethical standards and practices.

- Focus: Strengthening international collaborations through bodies like the United Nations or OECD to harmonize AI regulations and ethical standards globally.

5.Environmental Impact:

- Carbon Footprint of AI: The intensive computational requirements of AI can significantly contribute to carbon emissions.

- Focus: Developing incentives for companies to adopt green computing practices, including tax breaks for using renewable energy sources and penalties for high carbon footprints.

6.Inclusivity and Representation:

- Diverse AI Development: A lack of diversity in AI development teams can result in systems that fail to address the needs of diverse populations.

- Focus: Encouraging diversity through policies that mandate inclusive hiring practices and support underrepresented groups in STEM fields.

Collaboration and Multistakeholder Engagement Effective risk mitigation in decentralized AI requires the collaboration of diverse stakeholders to foster comprehensive and inclusive solutions:

- Public-Private Partnerships (PPP): Engaging in PPPs to combine the strengths of government, industry, and civil society in developing and implementing AI policies and standards.

- Main Idea : The Partnership on AI brings together academia, industry, and civil society to ensure AI benefits all of humanity.

- Possible Tangible Frameworks:

- OECD Principles on AI: Guidelines for public-private collaborations to foster trust and accountability.

- Deliberative Democracy Mechanisms: Using mechanisms such as citizen assemblies and stakeholder forums to involve a broad range of voices in the decision-making process, ensuring diverse perspectives and needs are considered.

- Main Idea: The Montreal Declaration for a Responsible Development of AI involved citizen consultations to define ethical AI guidelines.

- Possible Tangible Frameworks:

- Deliberative Democracy Frameworks: Such as participatory budgeting and citizen juries.

- Global AI Coalitions: Participating in global coalitions that promote collaborative research, policy harmonization, and the sharing of best practices across countries and sectors.

- Main Idea: The Global Partnership on AI (GPAI) works to bridge the gap between theory and practice in AI governance.

- Possible Tangible Frameworks:

- UN’s AI for Good Global Summit: Provides a collaborative platform for AI innovation aligned with sustainable development goals.

Strategic Policy Areas for Long-term Development

-

Ethical AI in Governance:

- Public Sector AI Use: Governments increasingly use AI for public services, raising ethical concerns about transparency, fairness, and accountability.

- Focus: Creating oversight bodies that evaluate the ethical implications of AI use in the public sector and ensure compliance with ethical standards.

-

AI in Global Health:

- Healthcare Equity: AI has the potential to improve healthcare access and outcomes but also risks exacerbating disparities if not implemented equitably.

- Focus: Developing policies that ensure equitable access to AI-driven healthcare solutions, particularly in underserved and low-income regions.

-

Blockchain for Social Good:

- Decentralized Governance: Blockchain's potential for decentralization can democratize governance but also risks creating unregulated spaces.

- Focus: Crafting regulations that balance the benefits of decentralization with the need for accountability and oversight in blockchain applications.

Governance Solutions in Tech Part III: Decentralisation and AI -- A Plausible Solution

In an era where opaque decision-making by AI systems raises profound ethical concerns, decentralised AI offers a beacon of hope. By leveraging decentralized architectures, we can dismantle the "black box" nature of traditional AI, fostering systems that are inherently transparent and accountable. This transparency ensures that every decision, every algorithmic nuance, is auditable, enabling stakeholders to trust the integrity of these systems.

Equity and Fairness

The centralized development of AI has often perpetuated systemic biases, disproportionately affecting marginalized communities. Decentralized AI provides a novel avenue for promoting equity by incorporating diverse datasets and fostering collaborative model development. By democratizing AI's creation process, we ensure that fairness is not a peripheral consideration but a foundational principle.

Privacy and Data Sovereignty

In a world increasingly concerned with data privacy, decentralized AI champions the cause of data sovereignty. By empowering individuals with control over their data, decentralized AI mitigates privacy risks inherent in centralized systems. Techniques such as federated learning and zero-knowledge proofs stand at the forefront of this revolution, ensuring that privacy and innovation are not mutually exclusive.

Moral Responsibility and AI Governance

Decentralized Ethical Governance

The governance of AI systems must evolve beyond the confines of corporate boardrooms. Decentralized governance models, particularly DAOs, democratize decision-making, allowing a diverse array of stakeholders to participate in shaping AI's ethical trajectory. Token-based voting systems, coupled with transparent governance frameworks, distribute moral responsibility equitably, fostering a culture of collective ethical stewardship.

Ethical Dilemmas in Autonomous Systems

Autonomous AI agents, operating within decentralized networks, present unique ethical challenges. These agents must navigate complex scenarios where human values and AI logic may conflict. Addressing these dilemmas requires the establishment of robust ethical frameworks, guiding these agents toward decisions that harmonize with societal norms and values.

Socioeconomic Impacts and Ethical Considerations

Impact on Employment and Labor

The advent of decentralized AI heralds a transformation in the labor market, raising ethical questions about employment and economic equity. While there is potential for job displacement, decentralized AI also opens avenues for new forms of work and collaboration. Ethical guidelines must be developed to facilitate a smooth transition, ensuring that the benefits of AI are equitably distributed.

Global Equity and Access

Decentralized AI must not become the privilege of the few. Ensuring global equity and access is an ethical imperative. By designing decentralized systems that are inclusive and accessible, we can bridge the digital divide, empowering underrepresented communities and fostering a more equitable technological landscape.

Risk Assessment in Decentralized AI

Risk Identification and Mitigation

Technical Risks

Decentralized AI is not without its technical challenges. Scalability, interoperability, and security are critical risks that must be addressed. Implementing robust cryptographic techniques and decentralized consensus mechanisms is paramount to safeguarding these systems against vulnerabilities.

Social and Ethical Risks

Bias amplification, misinformation, and potential misuse are significant social risks associated with decentralized AI. A comprehensive approach to risk assessment—including ethical audits and impact assessments—is essential to preemptively identify and mitigate these threats, safeguarding the societal fabric.

Policy and Regulatory Implications

Balancing Innovation and Regulation

Striking the right balance between innovation and regulation is a delicate endeavor. While decentralized AI holds transformative potential, it must be guided by regulatory frameworks that prevent misuse without stifling innovation. Self-regulatory mechanisms within decentralized networks can complement formal regulations, fostering a responsible innovation ecosystem.

Global Regulatory Challenges

The decentralized nature of AI poses unique regulatory challenges across jurisdictions. A collaborative, international approach is necessary to develop consistent regulatory frameworks that respect the decentralized ethos while ensuring compliance with global standards.

Scenario Planning and Risk Management

Future Scenarios

The future of decentralized AI is replete with possibilities, each carrying its own set of risks and opportunities. By engaging in scenario planning, we can anticipate potential developments, assess their risks, and devise strategies to navigate these uncharted waters effectively.

Crisis Response and Resilience

Building resilient decentralized AI systems is crucial for enduring crises, whether they stem from cyber-attacks or governance failures. Proactive measures to ensure system integrity and continuity will be pivotal in maintaining trust and stability in the face of adversity.

This sophisticated exploration of decentralized AI's ethical and risk dimensions underscores the necessity of a thoughtful, collaborative approach. As we stand at the crossroads of technological evolution, it is imperative that we navigate these challenges with a commitment to ethical integrity and proactive risk management.